what methods are used for gay rights movement to achieve their goals?

On April 25, 1965, 3 teenagers refused to get out Dewey's Eating place in Philadelphia after employees repeatedly denied service to "homosexuals and persons wearing nonconformist wear," according to Drum magazine, which was created by the Janus Club, an early gay rights group.

The teens were arrested and charged with hell-raising conduct, and Janus Club members protested outside of the eating house for the next five days, co-ordinate to Marc Stein, a history professor at San Francisco State University.

"Every single element of what we know of every bit Pride and gay rights and, especially, the pre-Stonewall homophile movement, was borrowed from the Blackness Freedom Motility."

Eric Cervini, LGBTQ Historian

"Unlike and so many other episodes, it kind of combined issues of homosexuality and trans issues," Stein, author of "Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement," told NBC News.

On May 2, three more people staged a 2nd demonstration at Dewey'southward. Though the restaurant called the law, the protesters weren't arrested, and subsequently a few hours they left voluntarily, co-ordinate to a Janus Lodge newsletter. The Gild wrote that the protests and sit-ins were successful in preventing future denials of service and arrests.

The sit-in at Dewey'due south is among a long list of examples that show a "direct line" to the Black civil rights motion, according to Stein. Specifically, sit-ins organized by gay activists in the '60s appear to exist directly inspired by protests held in 1960 by Black higher students at Woolworth'due south lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, against racial segregation.

Early LGBTQ activists (though they didn't apply that acronym at the fourth dimension) adopted many of the civil rights motility's strategies, Stein said, and they relied on much of the foundation laid by Black civil rights activists.

But the two movements weren't necessarily carve up — they ofttimes overlapped — and so influence happened in a few means, Stein said.

"Influence tin can be the influence of ideas, and specifically, ideologies, influence of strategies," he said. "Influence tin can also come up in the form of people who move betwixt movements, or who are engaged in multiple movements, and nosotros do accept examples of that in the early LGBT movement."

The influence — or 'plagiarism' — of ideas

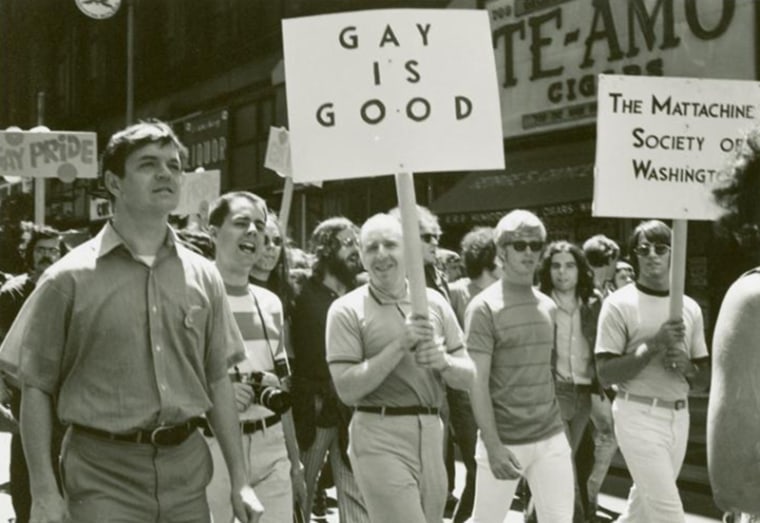

Queer activists were building a motion long before the 1969 Stonewall uprising in New York City, which is widely referred to as a turning point in the LGBTQ rights movement. Though Stonewall was a pivotal moment, activists like Frank Kameny were organizing for gay rights well before.

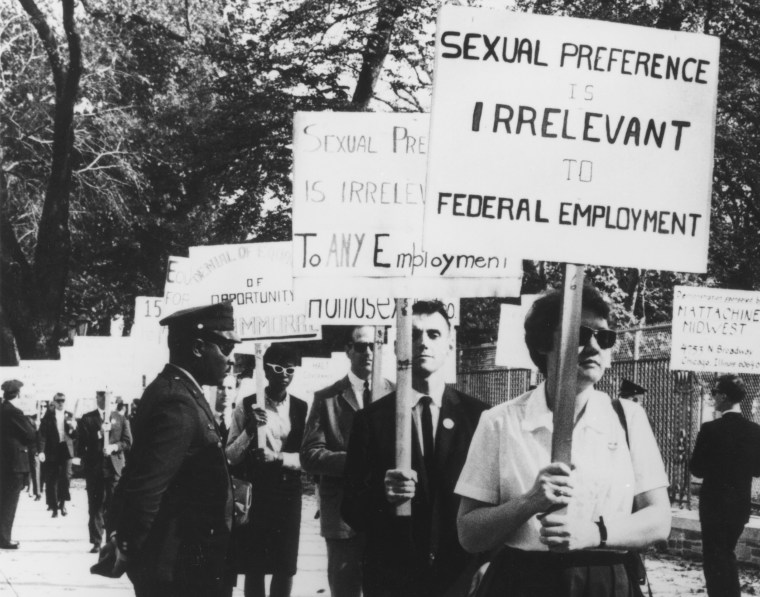

Kameny co-founded the Mattachine Lodge in Washington, D.C., ane of the first homophile groups ("homophile" being the adjective of option at the time), and he drew strategies directly from the Black civil rights movement, co-ordinate to Eric Cervini, a historian and author of "The Deviant's War," which focuses on Kameny and the early gay rights motion.

"Every single chemical element of what nosotros know of every bit Pride and gay rights and, particularly, the pre-Stonewall homophile move, was borrowed from the Black Freedom Movement," Cervini said. "Frank Kameny's primary role, what made him so brilliant but likewise complex of a historical figure, was that he served primarily as a Xerox machine copying dissimilar elements of the Blackness Liberty Movement and applying that to a previously nonmilitant, nonprotesting movement."

For example, Cervini said Kameny and a delegation of eight Mattachine Society of Washington members attended the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his "I Accept a Dream" oral communication. The march was organized by Bayard Rustin, who had been arrested in 1953 for having sexual activity with another man. In 1963, Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-Southward.C., a segregationist, chosen Rustin a "sexual debauchee" on the Senate flooring in an effort to discredit the march, according to Out History.

Kameny and the delegates saw that, fifty-fifty though Rustin had been exposed, 200,000 Americans still attended the march, and information technology became a historic moment, according to Cervini.

"So these white gay activists, who previously had been refusing to take to the streets, looked effectually and said, 'Maybe it's time, maybe not correct now, but maybe in the virtually future,'" Cervini said. (In fact, in 1979, activists would organize a National March on Washington for Gay and Lesbian Rights, which drew an estimated 200,000 protesters, according to the National LGBT Chamber of Commerce).

Inside a year of the 1963 march, gay rights activist Randy Wicker began picketing the U.Due south. Army Induction Center in New York Metropolis, and a few months after that, Kameny began picketing the White Firm and Philadelphia'south Independence Hall. Cervini also noted that Kameny modeled his phrase "Gay Is Good," which was used on protest signs and buttons, on the Black Power movement's "Black Is Beautiful."

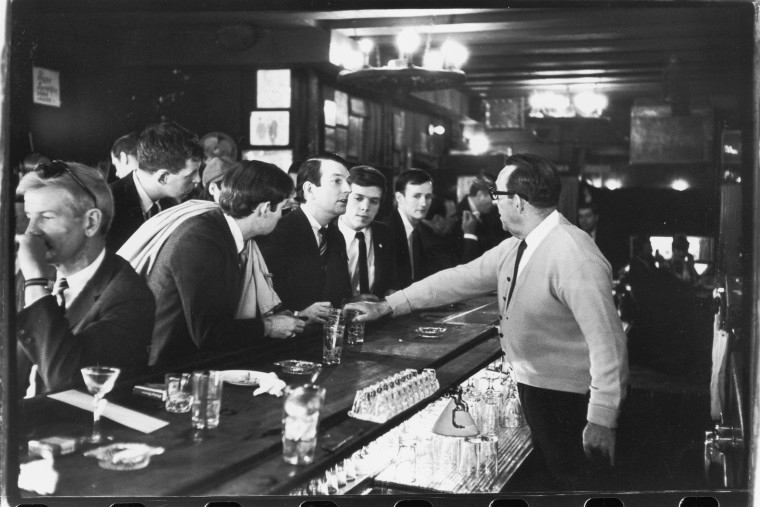

A few years later, in 1966, Wicker and three activists with the Mattachine Lodge's New York Metropolis chapter organized a "sip-in" at Julius' Bar to challenge a New York State Liquor Authority rule that said bars couldn't serve "disorderly" customers. In practice, bars would reject to serve LGBTQ people out of fear that they'd lose their liquor license. The sip-in, like the sit down-in at Dewey'south, used the same tactics as the college students at Woolworth's lunch counter, co-ordinate to Stein.

Stein said Blackness civil rights move strategies also affected how early LGBTQ activists conducted peaceful demonstrations. A coalition of gay and lesbian organizations held a yearly peaceful protest at Independence Hall chosen the Annual Reminder from 1965 to 1969, which Stein said were influenced by the early civil rights demonstrations in which demonstrators were instructed to dress respectably, with women in dresses and men in suits.

Cervini said civil rights demonstrators dressed upward equally a "reclamation of morality that was then effective when y'all look at the images of Montgomery or Birmingham or Greensboro." He said Time magazine even drew attention to the fact that immature civil rights activists looked similar they were going to church building, and, as a result, "How tin can you possibly claim that those Southern whites are the ones protecting morality?" he said. "So the early gay activists tried to emulate that aforementioned tactic, by using respectability equally a political tool."

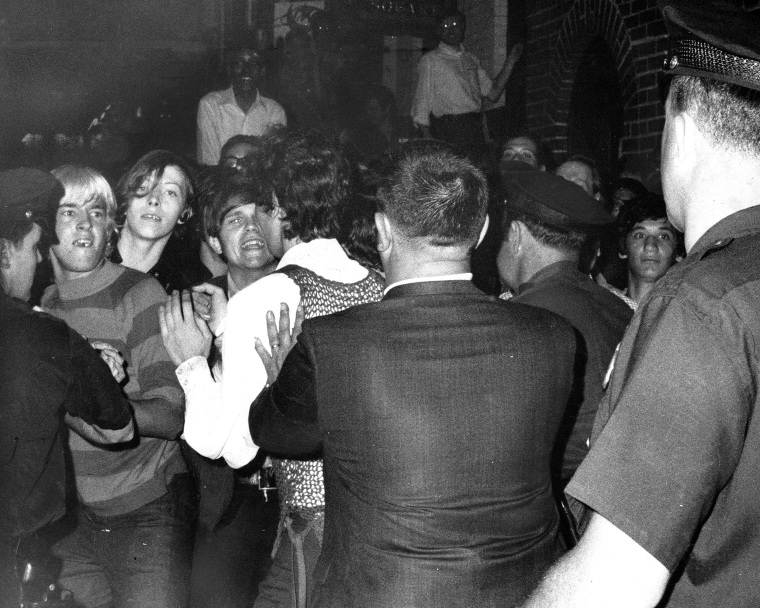

On the other hand, gay and trans activists were besides affected past the Black Power movement and urban uprisings, according to Stein. He said LGBTQ rebellions similar the 1966 Compton's Cafeteria riot in San Francisco and the Stonewall insurgence a few years later were likely influenced by events like the 1965 Watts Rebellion in Los Angeles, where 6 days of riots erupted betwixt police and the predominantly Black community.

"I would argue that the Black Power move was just as influential as the civil rights movement," Stein said. "Black Ability ideologies and strategies came to influence the motility very much so in the 2nd one-half of the '60s and so into the '70s, so there were both of those influences — peaceful, respectable demonstrations on the one hand, and a more aggressive militant action sometimes including riots on the other."

Cervini said FBI reports explicitly connect the Black Liberty Motility and the early homophile motility.

"We tin connect those two movements — Bayard Rustin, Frank Kameny and Randy Wicker — through FBI surveillance, and from informants within these organizations," Cervini said. "They were the ones informing the FBI that the gays, the homosexuals were learning from and discussing copying the Blackness Freedom Movement."

"This idea of a coalition between these two organizations — that the Blackness Freedom Movement might exist inspiring this other group of American citizens who are also marginalized, and the fact that they may both be taking to the streets, perhaps in coordination — that is what scared them the nearly," Cervini said of the FBI and Southern racist segregationists.

Nonetheless, the homophile movement, at to the lowest degree in New York and Washington, never made that coalition a reality, Cervini added.

He said he uses the discussion "plagiarism" to describe how Kameny used civil rights tactics without working with or crediting the activists whose tactics he used.

"You are using and borrowing tactics from some other movement, just not giving proper credit and non making infinite for people at the intersection of those two movements," Cervini said. "I think information technology raises the question of the moral acceptability of that."

Influence by intersection

In some cities, in that location was more of a coalition and less borrowing. The idea of 1 motion having an "influence" over the other could give the false notion that the fight for Black civil rights was comprised entirely of Black activists and the fight for LGBTQ rights was solely made up of whites, cautioned Steven Fullwood, co-founder of the Nomadic Archivists Projection, which documents and preserves Black history.

"At that place'south Black people in parts of both of those movements," Fullwood said, noting that there were Black people involved in both the Mattachine Lodge and Daughters of Bilitis, the showtime lesbian rights group.

Fullwood besides mentioned Marsha P. Johnson, who is credited as being a central figure in the Stonewall uprising, and Cervini cited Ernestine Eckstein (also known equally Ernestine Eppenger), who was active in the Black Liberty Motility and the Daughters of Bilitis in the '60s.

Stein also gave the example of Kiyoshi Kuromiya, a Japanese-American, anti-war activist who participated in the Annual Reminders at Independence Hall and had previously gone Southward and participated in civil rights marches. Kuromiya co-founded the Gay Liberation Front's Philadelphia chapter and became a spokesperson for a homosexual workshop at the Blackness Panther's Revolutionary People'south Ramble Convention in September 1970, according to Stein.

He gave a presentation "to the huge audience of the convention to applause," Stein said of Kuromiya, citing this as ane of many examples showing that the movements weren't fragmented or divided at the fourth dimension in some cities.

"They were uniting against police violence, state repression, capitalist exploitation and, later on all, the Stonewall rebellion was at least in part about a business exploiting its gay, trans customers," Stein said. "And then it kind of illustrates the way those issues came together at those particular episodes."

"Whatever movement that does not accept into business relationship the intersectional approach is never going to reach true liberation."

Steven Fullwood, Nomadic Archivists Project

Some of the major LGBTQ demonstrations, including the 1965 sit down-in at Dewey'southward Restaurant, took place in racially various communities, according to Susan Stryker, a scholar of queer and trans history.

She said the sit-in is an example of tactics adult in the Blackness civil rights struggle "becoming useful in situations that are not organized specifically around race, but are organized around questions of sexuality and gender expression and gender presentation."

"Then, is that a borrowing of civil rights tactics?" Stryker asked. "Or is it people who are perhaps familiar with this in unlike contexts of their ain lives saying … 'We need to do the same thing on this issue'?"

Stryker said there was besides a huge overlap between people who were organizing for racial and economical justice and queer and trans rights in the 1966 Compton's Cafeteria anarchism, which she described as "one of the first instances that we know well-nigh of militant trans resistance to police-based oppression."

The legal blueprint

Many major legal gains for LGBTQ people are also in role due to arguments adult by civil rights lawyers.

"The legal strategy challenging racial segregation, which was pioneered by the NAACP in the 1940s, was really the wellspring from which the LGBTQ equality move grew," said Alphonso David, a civil rights lawyer and the offset Black president of the Man Rights Entrada, the country's largest LGBTQ rights grouping.

In the 1940s and '50s, Thurgood Marshall, who led the NAACP, spent a decade challenging segregation on public transportation, in restaurants and in public schools, David said. Marshall argued a number of cases related to segregation, so in the mid-'50s he argued Dark-brown v. Board of Education in front end of the Supreme Court, which ruled that U.Due south. country laws segregating schools were unconstitutional.

"It took more than than a decade of litigation and argument testing combined with really a lot of sweat equity and strategic partnerships with grassroots organizers to successfully challenge racial segregation in the U.S. Supreme Court," David said.

Marshall's legal strategy, which involved using the due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Subpoena, served as a model that the LGBTQ movement used to challenge the criminalization of homosexuality and the denial of marriage rights.

"We are indebted to the civil rights leaders of the past, because they were really instrumental in outlining the essential objective, which was the guarantee of equal protection and how that should apply to all of us," David said.

Gay rights lawyers likewise congenital on major Black civil rights decisions to attain same-sexual activity marriage, according to David. In 1967, the Supreme Court held in Loving v. Virginia that laws banning interracial marriage violate the due process and equal protection clauses. "In that case, the Supreme Court held that, yes, there is a fundamental correct to ally," he said.

This same statement was successfully used nearly half a century afterward in Obergefell v. Hodges, David said, where information technology was argued that "denying same-sex activity couples the right to marry violates both the due process and the equal protection clauses of the U.Due south. Constitution — and we won."

"So that is one perfect example where you lot see the arguments that were advanced during the ceremonious rights struggle to at least recognize equality for racial minorities being used and applied in the context of LGBTQ people," he added.

'The aforementioned goal'

At that place has been meaning overlap between the ceremonious rights and LGBTQ equality movements, Fullwood said, and that'south a key takeaway.

"What we have to appreciate is that the arguments that were used in the civil rights movement in the 1960s involved LGBTQ people," Fullwood added, citing a speech given by Black Panther Political party founder Huey Newton in 1970.

Outlining the group's position on the ii emerging movements, Newton wrote: "Whatsoever your personal opinions and your insecurities near homosexuality and the various liberation movements amidst homosexuals and women (and I speak of the homosexuals and women as oppressed groups), we should effort to unite with them in a revolutionary fashion."

Today'south activists, Fullwood said, take to think almost the LGBTQ equality movement equally involving Blackness people and the racial justice movement as involving LGBTQ people.

"Whatever movement that does not take into business relationship the intersectional arroyo is never going to achieve true liberation," he said. "The Blackness and the LGBTQ movements have the same goal."

Fullwood said he's pleased with the kinds of activists who are engaging multi-event platforms that "call for dissimilar, insightful means to resist oppression," only that he'southward occasionally run into the phrase, "This isn't your grandmother'due south movement."

"If that's the sentiment, I say this: Y'all better hope it's your grandmother's movement, because she and thousands like her made information technology possible for you to have the linguistic communication, perspective and insights that you enjoy today," he said. "This is not new. Read. Research. Build. You be in a river of resistance. Know and embrace that history. Information technology'due south waiting."

Follow NBC Out on Twitter, Facebook & Instagram

Source: https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/different-fight-same-goal-how-black-freedom-movement-inspired-early-n1259072

0 Response to "what methods are used for gay rights movement to achieve their goals?"

Post a Comment