What Does Stanford Argues in Her Review in the Nashville Shoe?

Embracing Multifariousness: Where does Stanford get from hither?

past John Luttig

In 1968, Stanford opened its residential doors to the Ceremonious Rights Move. As the movement towards racial integration swept the nation, Cedro became the first black themed dorm at Stanford. After a serial of housing shifts during the mid-70s, the black-themed dorm became the current-mean solar day Ujamaa, which maintains that to this solar day, fifty percent of its residents are blackness students.

Ten years afterward, the energy behind the Civil Rights Movement translated into the college admissions processes of schools beyond the land. In the landmark Supreme Courtroom decision Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the Supreme Court decided in a 5–4 split that while explicit quotas for racial groups in admissions are impermissible, it is legal to consider race as a gene in the college admissions process. The Supreme Court upheld the controversial decision in another 5–4 split in Grutter v. Bollinger in 2003, after receiving overwhelming back up in the form of 69 amicus briefs from universities and other academic institutions in favor of upholding the Academy of Michigan Law Schoolhouse's admissions policy. Conversely, there were only 15 amicus briefs — none of which were from universities — in favor of hit down affirmative action. Proponents of affirmative action stated, amid other points, that racial diversity brought "a robust exchange of ideas".

Stanford has taken authoritative measures to keep its campus racially diverse. Stanford's Multifariousness and Access Function provides Staff Groups for its current minority staff members and develops the Affirmative Action Plan for the university each twelvemonth. Similarly, Stanford offers resources for traditionally underrepresented groups in the undergraduate community through the Title IX office, Black Community Services Middle, and the diverse themed houses effectually campus including Ujamaa, Okada, Casa Zapata, and Muwekma-Tah-Ruk.

These resources strive to maintain the racial variety that Stanford touts in its recruitment process. Stanford seems to be accomplishing its goal of promoting racial and socioeconomic diversity in its admissions through affirmative activeness, advancing one of the university's core beliefs that "students benefit from unparalleled diversity of thought, experiences, cultures, and ways of viewing the world." Racial diverseness contributes to the accomplishment of this goal given the inevitably different backgrounds of a racially diverse population, but the next step in furthering Stanford's diversity is to focus on "diversity of thought".

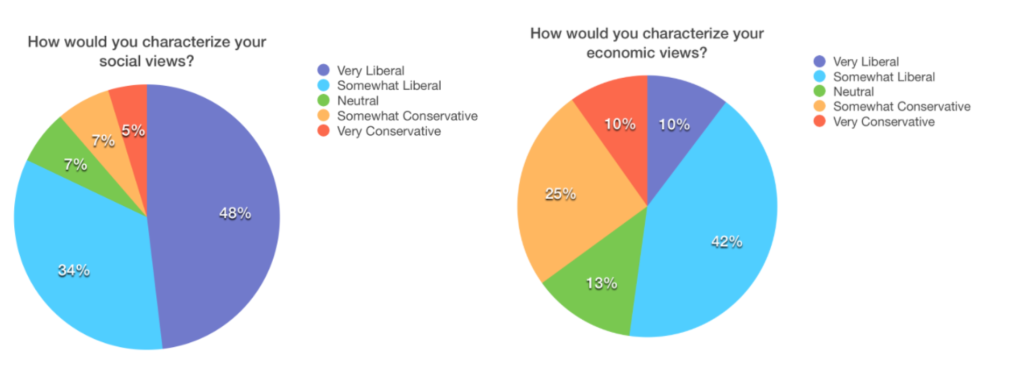

Stanford has a long manner to go in realizing its goal of diversity of thought, starting with the freshman experience. For freshmen interested in a more than traditional liberal arts pedagogy, Stanford offers the Structured Liberal Didactics program. SLE'south program overview claims that it "encourages students to alive a life of ideas in an atmosphere that emphasizes critical thinking and interpretation." Interestingly, in an bearding survey of 44 SLE students at Stanford, 61 percent of respondents self-identified their economic political views as "somewhat liberal" or "very liberal". In the same grouping of respondents, 89 percent of respondents claimed to have "somewhat liberal" or "very liberal" views on social policy.

Similarly, 64 percent of SLE respondents noted that their professors are somewhat or very liberal. These numbers may have implications in the classroom that conflict with the notion of an intellectually diverse community. For students seeking a well-balanced education, it is important to consider the possibility that, given these statistics, an plain "robust substitution of ideas" may finish up being a debate between two liberal perspectives. These debates may create the impression of intellectual diversity, even though the perspectives offered may just be different shades of liberalism.

This distortion extends beyond the classroom. In a survey of 219 Stanford students conducted final week, 48 percent of respondents identified their views on economic policy as somewhat or very liberal, while a whopping fourscore percent of respondents said the same near their social views. In the aforementioned survey, still, 85 per centum of respondents claimed that their friends are somewhat or very liberal — more than either self-identified percentage. This suggests that on average, people think that their friends are more than liberal than themselves, both fiscally and socially. One possible explanation is that the student body is aware that conservative viewpoints are in the minority, and therefore those who hold those views practice not speak up. This further encourages people to primarily express their more than liberal views to their friends, creating an even tougher environment for conservative viewpoints to exist voiced.

There seems to be a somewhat polarizing outcome in the departure between students' actual views and the views they perceive their friends to take. As time goes on, fewer students identify every bit liberal. While 83 percent of freshmen identified as somewhat or very socially liberal, just 62 percent of juniors identified equally somewhat or very socially liberal. Similarly, 52 percent of freshmen place as having somewhat or very liberal economical views, while 39 percentage of juniors identify as such. While this survey deals with ii unique populations instead of tracking one sample size over its undergraduate career, the respective 21 pct and xiii percent drops in social and economic liberal association are meaning.

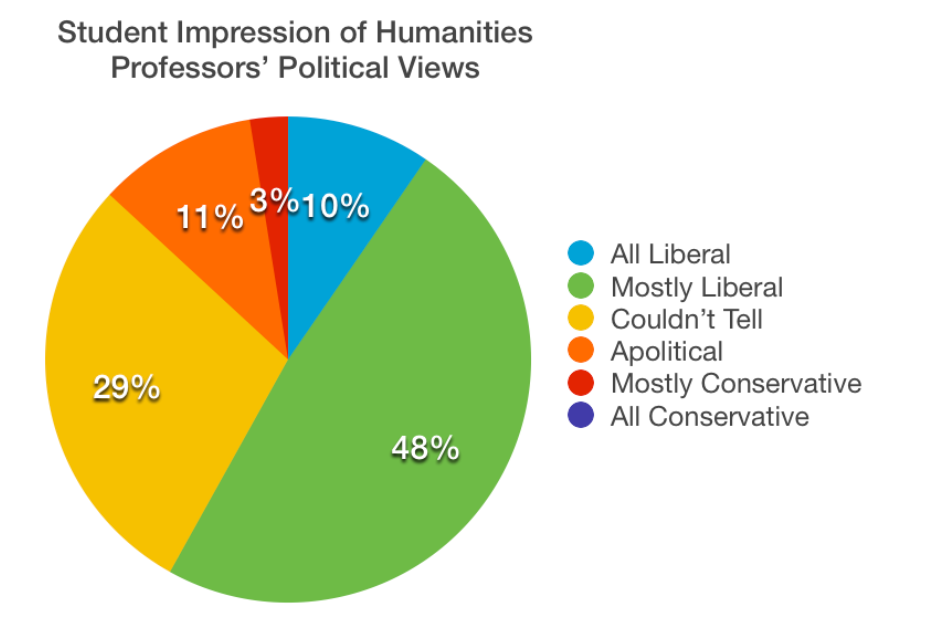

In the survey, respondents were also asked to approximate their humanities professors' political leanings based on their interactions with them in class. 53 percent of students claimed that their professors were either all or mostly liberal, and 45 of the other 47 percent of students either couldn't tell or thought their professors were apolitical. When over half of students notice that their professors are mostly or all liberal, and the students themselves are generally liberal, information technology can lead to class discussions that are not every bit intellectually various as Stanford might promise. Of course, liberal professors are not necessarily precluded from being impartial give-and-take leaders, but it seems dubious that all or even nearly are, given that 57 per centum of students easily identify all or most of their professors as liberal. Similarly, students may brand liberal arguments to appeal to professors that they perceive as being liberal.

It tin can sometimes exist difficult to participate in intellectual discourse if y'all know that few people agree with you lot. Unsurprisingly, of those who identified as somewhat or very socially bourgeois, 57 percent said that fewer people at Stanford concur with them during political discussions.

This survey suggests both that Stanford students may be a fleck more conservative than they are willing to express to their friends, and that a strong bulk of professors are at least perceived to exist liberal by their students. When creating the university, the Stanfords wrote in the Founding Grant that the university should encourage "the studies and exercises directed to the tillage and enlargement of the listen." While Stanford's motion towards racial diversity in creating residential and academic opportunities for minorities partially accomplishes this goal, it is important to consider that intellectual diversity may be the next step required to achieve this balanced education — and that Stanford may be far from reaching it.

Source: https://medium.com/stanfordreview/embracing-diversity-where-does-stanford-go-from-here-330118f4a70e

0 Response to "What Does Stanford Argues in Her Review in the Nashville Shoe?"

Post a Comment